Over the past few decades, the interests of biofuel and aviation producers have focused on the use of biodiesel as a means of reducing the carbon footprint of jet engines. The ethanol industry wants to get more involved and is creating a new industry. The SAF market is expected to dominate the field over the next few decades.

Sustainable Aviation Fuels SAFs [Sustainable Aviation Fuels] are liquid hydrocarbons derived from non-oil sources, including ethanol. SAFs currently account for less than 1% of the jet fuel market, but they do not require major changes to existing jet engines or refuelling infrastructure.

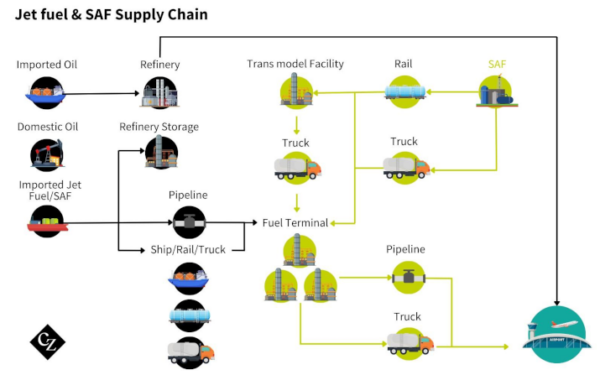

Jet Fuel and Clean Aviation Fuel [SAF] Supply Chain

To allow ethanol producers and the US agricultural sector to participate in the SAF market, the US EPA must first finalise the GREET [Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation] model. The model is a tool that examines the lifecycle impacts of technologies, fuels, products, and energy systems on vehicles and has been under review since 2019.

GREET analysis clarifies the energy and environmental benefits of biofuels, bioproducts, and bioenergy, and identifies opportunities to address barriers to their sustainable use. U.S. officials are currently working on modifications to the GREET model for SAF. This model is important for determining eligibility for the SAF tax credit under the [US Inflation Reduction Act’s SAF tax credit].

Grain ethanol is the most common and cost-effective source for large-scale SAF production. With nearly 200 bioethanol refineries located in the US, a well-established transportation and storage network, and the capacity to produce nearly 68 billion litres per year of low-carbon renewable fuel, everything is already in place to increase ethanol production for jet fuel.

Ethanol producers are unhappy with delays in finalizing the model. Renewable Fuels Association [RFA] President Jeff Cooper said that while the association is pleased to hear about the progress being made on the GREET model update, it is frustrated by the delay in making changes that should have been completed by March 1. RFA urged the working group to complete the process as quickly as possible while maintaining scientific integrity and honoring commitments to implement carbon reduction strategies.

Airlines are backing SAF:

- Delta Air Lines recently said SAF is the most promising lever known to date to accelerate the aviation industry on its path to zero carbon emissions by 2050.

- Irish carrier Ryanair said this month it will receive an additional 500 tonnes of SAF from Austrian energy company OMV in 2024. British airline Jet2 said it will use a SAF blend at Bristol airport in 2025, a year ahead of the UK government’s SAF mandate.

- In Spain, local airline Volotea said it operated its first flight on 13 March using 50% SAF fuel supplied by Spanish oil company Repsol.

The US government wants the aviation industry to use at least 11 billion litres of SAF a year by 2030.

Meanwhile, Brazilian corn-based ethanol producer FS has announced it has received certification that its corn-based ethanol meets international requirements for SAF production. The ISCC Corsia International Sustainable Carbon Certification covers its Lucas do Rio Verde unit in Mato Grosso. ISCC is the leading international biomass and bioenergy certification system focused on land use sustainability and greenhouse gas (GHG) tracking and verification.

In addition to the general ISCC Corsia certification, FS also received an additional low risk LUC [Certification of low use change] certification, confirming that the use of biofuels does not result in greenhouse gas emissions associated with indirect land use change ILUC [indirect land use change], which can occur when pasture or farmland previously dedicated to food and feed markets is used for biofuel production

SAF could be a driving force for ethanol from corn. If SAF production can be increased, it will create an important new demand driver for ethanol from corn. However, the U.S. is delayed in finalizing the guidelines..

Brazil’s 18% customs duty on U.S. ethanol

In a letter recently sent by 20 members of Congress to President Biden and the USTR [US Trade Representative], it was noted that the US exports approximately 11 billion gallons of ethanol worth $4 billion and 11 million tonnes of DDGS worth $4 billion annually. The letter cited several countries that have created barriers to ethanol exports from SA, including Brazil, which imposed an 18% tariff on US ethanol imports, and India’s ban on fuel ethanol imports.

Sales of U.S. ethanol to Brazil were virtually duty-free from 2011 to 2017. However, Brazil imposed a tariff quota from 2017 to January 2022 and then a 20 per cent Mercosur general external tariff on ethanol imports from Jan-2022. The tariff was suspended on 21-Mar-2022 but reinstated at 16% in Jan-2023. In 2024, Brazil raised tariffs on ethanol imported from the US from 16% to 18%. As a result, Brazil’s imports of US ethanol fell from 490 million in 2018 to 30 million gallons in 2023.

At the same time, Brazilian ethanol has free (duty-free) access to the U.S. market. Given this significant discrepancy in the historical commercial relationship between the countries, the U.S. ethanol industry is advocating for restrictive measures for the importation of Brazilian ethanol into the U.S. In particular, the U.S. is pushing to restrict the importation of Brazilian ethanol into the U.S. unless the country permanently eliminates tariffs on U.S. ethanol.

Despite intense pressure from the Biden administration, Brazil will continue to apply tariffs on U.S.-origin ethanol to protect its ethanol producers. Brazil’s tariff on ethanol imports raises the cost of fuel for domestic consumers, prompting the Brazilian fuel importers association ABICOM to formally request a duty reduction on U.S. ethanol in October 2023. Brazilian Agriculture Minister Carlos Favoro has stated that Brazil is willing to reduce tariffs if tariffs in the U.S. market would allow for increased ethanol production based on Brazilian sugarcane to produce cleaner jet fuel.

Ethanol producers fight European FuelEU rules

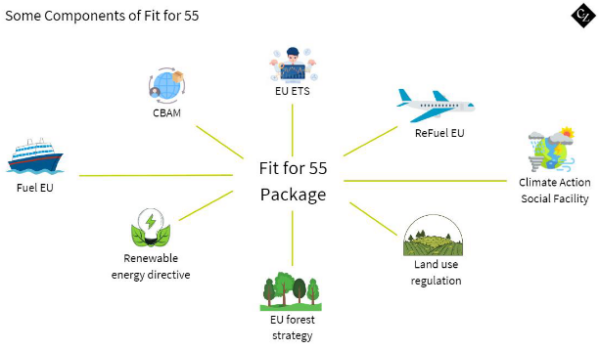

In July 2021, the European Commission launched the FuelEU initiative, part of the Fit for 55 programme, which aims to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, and achieve climate neutrality by 2050. The existing provisions were adopted in 2023.

The EU FuelEU shipping regulation equates fApril 02uel bioethanol with fossil fuels. The European Union claims that this regulation will prevent emissions from land use change and biodiversity loss. The FuelEU regulation effectively bans the use of renewable crop-based fuels as a decarbonisation tool, has irritated ethanol producers, they are outraged by the European Commission’s arbitrary assumptions and on both sides of the Atlantic are suing in courts hoping to overturn the relevant regulations adopted by the EU in 2023.

The initiative has been launched by ePURE, a Brussels-based trade association representing 44 European ethanol producers (around 50 plants accounting for 85 per cent of ethanol production in the EU27+UK), and one of Europe’s largest ethanol producers, Pannonia Bio. In April 2024, the American Renewable Fuels Association RFA came out in favour of ePURE and Pannonia Bio. The FuelEU rules are completely at odds with other programmes such as the RED [Renewable Energy Directive], in which the EU reaffirmed the low-carbon benefits and sustainability of bioethanol derived from plant crops.

China and its blending policy

China’s biofuels policy has been used primarily as a corn stockpile management programme, while air quality and environmental or climate change objectives have been secondary. High corn prices in 2023 meant that domestic corn-based ethanol producers were struggling to make a profit – $28/mt [the price of fuel ethanol is fixed legislatively at 91.1% of the retail price of gasoline by the NDRC]. Demand for fuel ethanol remained low and high PRC tariffs made its import unprofitable [MFN tariff on code 2207.10 Non-denatured ethanol 40%, on code 2207.20 Denatured ethanol 30%]. Compliance with PRC requirements for the production of E10 ethanol was weak, further reducing incentives for its use.

In 2017, the PRC announced that it would introduce a nationwide E10 standard by 2020. In 2019, the PRC delegated E10 blending targets and decision-making authority to provincial governments, while requiring existing E10 pilot areas to continue to blend into E10. At the end of 2020, this goal was informally suspended and since then, ethanol production rates in the pilot areas have declined.

By 2023, the PRC had not adopted any significant policies or measures to support or develop the ethanol industry, further evidence that the government’s priorities have shifted away from biofuel development. Fuel ethanol production in 2023 [22 plants with a total installed capacity of 7.72 billion litres, including 8 large plants built in 2018-2021] is estimated at 3.9 billion litres [49% capacity utilisation], slightly higher than in 2022 [+96 million litres]. Ethanol consumption 3.898 billion litres [imports 0, exports 2 million litres], national average blending rate 1.8% [gasoline 213.567 million litres]. Feedstocks used: maize 5.47 million tonnes (ethanol yield 41.7%) + rice 2.28 million tonnes (40%) + cassava dried chips 1.41 million tonnes (15-65%) + wheat 0.58 million tonnes (39.3%). There has never been a nationwide standard for biodiesel production at all.

Policy guidelines adopted by the PRC allow the country’s biofuels sector to be partially isolated from the global market and less susceptible to market forces. There are rumors that the PRC may unofficially move to mandate E5 in the coming years, although E10 remains the official policy. Actual blending rates vary and are often much lower even in regions where a provincial E10 program is in place.

India

Current total ethanol production capacity in India is: cane molasses feedstock 7.89 billion litres [263 plants] + grain 2.91 billion litres [129 plants] = total 10.82 billion litres [392 plants]. This capacity produced 6.30 billion litres of ethanol in 2023 [+19% to 2022], with a capacity utilisation of 57.3%. Fuel ethanol consumption in 2023 is estimated at 6.11 billion litres. Capacity requirement in 2025: cane molasses 10.79 billion litres + grain 5.31 billion litres = total 16.10 billion litres.

OMC storage capacity at the beginning of 2023 was 344 million litres, which translates to 6.28 billion litres of ethanol per year in 20-day storage. The main feedstock for ethanol production is B and C molasses from sugarcane, followed by sugarcane juice, spoilt food grains unfit for human consumption, surplus rice, corn and other potential feedstocks.

Mandatory blending of ethanol into petrol in India of at least 10% – the estimated blending rate in 2023 was 11.5% [petrol consumption 52.97 billion litres] which is a new record, the monthly average by the end of 2023 had risen to 12% – but in 2025 her national target should be 20%. To achieve this target, India needs to allow imports of fuel ethanol, which is currently banned, and bioethanol feedstocks. The US Trade Representative in India [USTR] will ask the country to stick to its E20 target.

UK

The UK moved to an E10 mandate in 2021. Since then, ethanol exports from the US have increased by around 400%, but from 2027, a cap is imposed on plant-based biofuels, which is gradually reduced from 7% to 2% over five years.

The UK government wants to move to a recycling-based system, which would effectively reduce the amount of US ethanol that can compete in this market. The US is urging the UK to change its restrictions on ethanol production from crop crops as demand for ethanol is expected to increase in the future from new markets such as cleaner aviation fuel.

Mexico lags behind in ethanol production

Although Mexico is the sixth largest producer of sugarcane in the world and the seventh largest producer of sugar, about 40,000 m3 of ethanol produced from this source is mainly consumed by the alcohol industry. As a producer of the two main types of ethanol – sugarcane and corn – Mexico has the potential to become a major biofuel producer, but a number of obstacles, both regulatory and cultural, are slowing the development of what could be an important contribution to global efforts to reduce carbon emissions and slow the pace of accelerating climate change.

Mexico is one of the few countries in the Americas that has not introduced specific mandatory quotas for ethanol as a fuel. Mexican authorities have refused to revise the fuel quality requirements set by local standards since 2018. In 2020, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled against amending legislation that would have increased the proportion of ethanol in petrol to 10%. In 2021, Mexico’s Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), responsible for changing fuel standards, decided not to consider the issue. As of January 2024, the CRE has yet to take any action.

In addition to regulatory restrictions on ethanol production, the cultural barriers associated with using corn for anything other than food or animal feed are extremely important to the Mexican population. In the mosaic of Mexican culture, corn is not just a staple crop, it is a symbol of history and a cornerstone of a rich culinary heritage. In addition to its culinary uses, corn has important cultural and ceremonial significance. Corn is not just eaten, it is celebrated, and this tradition reflects the deep connection between the Mexican people and their land. And so, in Mexico, the use of corn to produce something as trivial as a fuel additive does not enjoy much public support.

Mexico will elect a new president this June. One of the two candidates running to replace him – and both are women – could bring to power a new administration that may be more concerned with how Mexico prepares for an uncertain future. The country may have an opportunity to modernise its outdated management and regulation of biofuels production.

© 2024, Insightex

Article adapted from https://app.czapp.com/auth/Frank_Zaworski and https://fas.usda.gov/data.

The article is copyrighted by Insightex, Ukraine.